Historical Background

Antioch of Syria is also known as Antioch on the Orontes because it was founded on the east side of the Orontes River in a plains region between the Mt. Casius in the southern part of the Taurus mountains and Mt. Amanus. After the conquest of Syria by Alexander the Great and his death in 323 B.C., Syria was controlled by one of his successors, Antigonus. But then in 301 B.C. another one of Alexander's generals, Seleucus I Nicator, defeated Antigonus and took control of Syria and established the city of Antioch next to the Orontes River in honor of his father Antiochus (it was 1 of 16 cities he named Antioch). The area of Antioch had already been a major trade route beginning with the Hittites in the 3rd millenia B.C. and so it was a natural location to build a trade city that would enhance commerce in the region and strengthen the empire.

Under the reign of the Greeks, Antioch grew and developed into a great cultural city of the empire. Rulers like Antiochus I Soter (281-261 B.C.), Seleucus II Callincus (246-225 B.C.), and Antiochus IV Epiphanes (175-164 B.C.) all devoted special attention to building and enhancing Antioch in Syria. Antioch was briefly capture in 83 B.C. by Tigranes of Armenia but it was soon taken over by the Roman general Pompey in 66 B.C. Antioch immediately became the capital city of the Roman province of Syria and was a popular city that was visited by many renowned Romans including Julius Caesar and Octavius Augustus. Of special note is that in 40 B.C. Antioch hosted the the celebrated imperial wedding between Marc Antony and Cleopatra.

By the end of the 1st-century B.C., Antioch had grown into a booming cosmopolitan city and was considered the third largest city in the Roman Empire (behind Rome and Alexandria in Egypt). It was a strategic city for military fortification, it was culturally diverse and attracted merchants from all over the empire, and it allowed the empire to be supplied with many resources, especially from the east.

According to Josephus, the famous Jewish historian, a large Jewish population was known to reside at Antioch since nearly its founding at the end of the 3rd century B.C. and they continued to establish a community their and integrate into the very fabric of the city. By the end of the 1st century B.C. it had been noted by Josephus that the Jews in Antioch has made many proselytes and formed a well accepted relationship with the citizens of the city (J.W. 7.45). However, several Jewish revolts against the Roman Empire were known to have occurred during this time, such as the attempt prompted by Antiochus IV Epiphanes to turn the temple in Jerusalem in a temple for Zeus in 167 B.C., which eventually lead to the Maccabean Revolt in 166 B.C. But also the revolt against Demetrius two decades later is known to have arisen specifically in Antioch. Furthermore, in the 1st-century A.D. When the Jewish rebellion against the Roman Empire led to the destruction of Jerusalem in 70 A.D., a group of Antiochene citizens made a request to Titus (the Roman general and future emperor) to expel all Jews from Antioch. When he refused, they lessened their request to have their religious privileges revoked and their civil freedom curtailed. But Titus further declined their impetuous desires (J.W. 7.96-111; Ant. 12.121-124).

Aside from Barnabas and Paul's work in the city of Antioch (which will be discussed below), Antioch played a crucial part in the movement of Christianity in the first several centuries. It is proposed that Antioch was the location for the writing of The Gospel of Matthew as we have our earliest evidence of the use of the Gospel in the writings of Ignatius (c. 35- c. 107 A.D.), who is claimed to be the third bishop of Antioch. In addition, two centuries later Antioch would be home to a prominent school of Scriptural interpretation known as the “Antioch School”, of which John Chrysostom (349-407 A.D.), the “golden-mouthed” preacher, was its chief proponent. The Antiochian School of interpretation stressed more literal and direct interpretation methods over against the Alexandrian School, which stressed allegorical interpretation of Scripture. Origen of Alexandria would be likely the best example representing that school of interpretation. The Antioch School of interpretation could be said to be most closely represented by the modern grammatico-historical method of interpretation.

Archaeological Significance

Archaeologists have a good idea of what the ancient city of Antioch looked like and how it was setup but there is very little left in plain view for the modern visitor. Archaeologists know (from findings and the writings of ancient historians) that the streets were organized in a grid pattern (called a Hippodamian road system), the streets were colonnaded, and main street ran through the city and was approximately 2 miles long. The Church of St. Peter, which resides at the base of Mt. Staurin adjacent to Mt. Silpius, is built below natural caves and rock carvings from the time of the ancient city. The site is traditionally said to be the meeting place of Peter and the first disciples in Antioch. It is confirmed that the caves were used as early as the 4th century for Christian meetings as dated by the mosaics discovered on the floor of the caves, but prior to that not much can be determined with certainty.

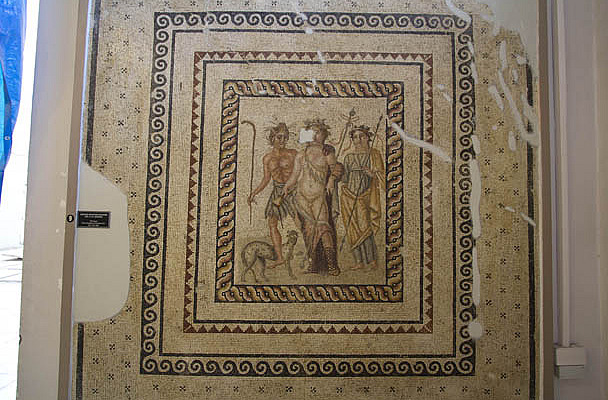

The impressive archaeological evidence left in Antioch is found at the Hatay Archaeological Museum where they house one of the largest and most famous mosaic collections in all of Turkey. The mosaics range form the 2nd - 6th centuries and are rich with color and detailed scenes. Most scenes are of mythological tales, animals, and/or nature.

THE GOSPEL HEADQUARTERS...

Biblical Significance

The city of Antioch first appears in the biblical text when Nicolas is mentioned as being “a proselyte from Antioch” (Acts 6:5). Nicholas was one of the seven men who were chosen by the disciples to assist the apostles in administration of food to the widows. Antioch is also mentioned as an initial location for preaching by Jewish disciples fleeing from the persecution following Stephen's death, and they were soon joined by Greek-speaking disciples from Cyprus and Cyrene who preached to the Gentiles in Antioch as well (Acts 11:19-20). In a response to the efforts of these disciples in Antioch, the leaders in the church at Jerusalem decided to send Barnabas to them in order to support and assist in the missionary work going on there (Acts 11:22). When Barnabas arrived in Antioch, he encouraged the believers and helped preach the gospel, and from his efforts with the other disciples, it is stated that “many people were brought to the Lord” (Acts 11:24).

Maybe Barnabas saw the harvest in Antioch greater than he could handle alone or maybe he just thought it was a good idea to get a newbies feet wet in that place, or maybe the Lord simply revealed his will to him...but whatever the case was, Barnabas takes off from Antioch and picks up Saul (later called Paul) in Tarsus and brings him back to Antioch with him and they remain there with the church preaching and teaching for one year (Acts 11:25-26). Barnabas and Paul must have really caused a stir and the Spirit of the Lord must have been moving powerfully among the disciples there because in Antioch the followers of Jesus were first called “Christians” (Acts 11:26b).

This term has been long recognized as a derogatory term aimed at insulting and mocking the followers of Jesus as though it was ludicrous to devote oneself to this person who claimed to be the Christ (thee Messiah). The Greek term Χριστιανός (Christianos), is an adjective formed with the Roman style Latin ending to denote an adherent, or a belonging to, or ownership. In essence, Christianos means “a Christ-follower”. In 96 A.D. Tacitus, the Roman senator and renowned historian, wrote, “The vulgar [pagans] call them Christians. The author or origin of this denomination, Christus, had, in the reign of Tiberius been executed by the procurator, Pontius Pilate” (Annal. 15.44).

After preaching in Antioch and have great results with the movement of the gospel, Barnabas and Paul decided to leave Antioch to bring a disaster relief gift to the disciples in Jerusalem because one of the disciples from Jerusalem named Agabus prophesied by the Spirit of the Lord that there would be a great famine in all the land. And so the believers in Antioch desired to send gifts to support the believers in Jerusalem during the upcoming famine. They entrusted their gifts to Barnabas and Paul and the two preachers then left Antioch and journeyed to Jerusalem (Acts 11:27-30).

At some point Barnabas and Paul returned to Antioch, and when the Spirit of the Lord revealed to the leaders of the church in Antioch that Barnabas and Paul were being called for a special task, they prayed over them and laid their hands on them and then sent them off to do the will of the Lord (Acts 13:1-3). Antioch was basically Paul's home base of operations throughout most of his itinerant preaching ministry. He specifically leaves and returns to Antioch on his first missionary journey (Acts 13:1-14:28), but during that time Luke records that some Jews from Antioch came to Lystra and convinced the crowd to stone Paul after they were just previously willing to sacrifice to him and Barnabas as gods since they healed a lame man (Acts 14:8-20). Paul also travels through Antioch on several other occasions and the city is mentioned in Acts 15:22-23 30, 35; 18:22.

Apart from the narrative of Acts, Antioch of Syria is mentioned in Paul's Letter to the Galatians as the location where he confronted Peter on account of Peter's hypocrisy when Peter withdrew from table fellowship with fellow Gentile believers (Gal 2:11-13). Paul says that Peter was afraid of the criticism from the friends of James (likely Jews that had come from Jerusalem to Antioch). Maybe Peter feared a d�j� vu of when he first went to Jerusalem and was reprimanded by other leader for his behavior of associating and eating with “unclean” Gentiles (cf. Acts 11:1-3). However, after explaining the vision the Lord had given to him, the Jerusalem leaders were very glad to hear that the Spirit of the Lord had fallen upon the Gentiles as well as on the Jews and they praised God together (cf. Acts 11:18).In the confrontation in Antioch, Paul describes how Peter's actions did not merely represent him alone; his decisions as a leader in the church influenced others and many other Jewish believers also followed in like suit and quit eating with their fellow uncircumcised Gentile believers. Peter's apprehension for fear of the Jewish believers that had come from James even convinced Barnabas to be lead astray and sin. Paul's accusation against Peter (and the other Jewish believers) addresses the root of the issue and exposes their hypocrisy before everyone when he says, “Since you, a Jew by birth, have discarded the Jewish laws and are living like a Gentile, why are you now trying to make these Gentiles follow the Jewish traditions?”

It is important to note that Peter was not reprimanded in the corner of the room or asked to step outside for a moment. Paul spoke out against his failure to follow the truth of the gospel in front of everyone because Peter's actions had affected others and both he and they were the ones in error.Sometimes, people are pressured into behaving certain ways in order to avoid social stigma, or in an attempt to find favor with people, or in order to be accepted or not be judged. Even the best leaders find themselves having to continually re-evaluate themselves so see if they are falling prey to destructive decisions that do not build the church up in the truth of the gospel. Leaders that believe they are above reproach are the ones who are the most blind to their course of actions. They are the most likely to stumble and make mistakes that will unknowingly ripple throughout the church. If these decisions are detrimental enough, it can begin to cause division within the church and people will begin to take sides and destroy the unity of the fellowship that Christ came to bring. Such hypocrisy often goes unnoticed because it is justified by other causes as being “in-line” with the truth. It is a subtle deception to pretend the truth can be suspended for other supposed godly means. Peter learned this first-hand because Paul had the nerve to stand up and point out the problem. The early church might have turned out much different if Peter had rejected Paul's correction and the church split there and then.