Historical Background

Lystra was a Roman city in south-central Asia Minor. It is thought to have been settled initially in the 2nd century B.C. being near the “King's Road” created by Darius I of Persia in the 5th century B.C. between Persepolis in Persia (modern Iran) and Sardis in Asia Minor (near modern Izmir). The King's Road transited through/near several cities in central Asia minor like Lystra, Iconium, and Pisidia Antioch. When the Romans conquered Asia Minor, Lystra, just like Antioch of Pisidia, became a Roman city in the empire. In 36 B.C. Lystra was also governed locally by Amyntas, the client king of Galatia. Lystra was in the region of Lycaonia which was absorbed into the Roman region of Cilicia, which fell under the jurisdiction of Amyntas at the time. When Amyntas died in 25 B.C. Lystra became part of the Roman region of Galatia and was declared a Roman colony, like Pisidia Antioch. More Roman militia were given land and retired there because populating Roman colonies with a Roman legion was Augustus' strategy for maintaining better control over Asia Minor. It is known that several mountain tribes in central Asia Minor, such as the Homandadenses, were resisting Roman rule and settling Roman soldiers (active and retired) in the province was an attempt to curtail their behavior and have local forces to quell any uprising.

When Lystra became a Roman colony and it became occupied with veteran Roman militia, it received the honorific name Julia Felix Germina Lustra. Also, a branch of the Via Sebaste (Sebastian Way) that ran from Pamphylia in the west of Asia Minor to Tarsus in the east ran next to Lystra on its way between Pisidia Antioch and Iconium. While most Roman colonies began to build and model themselves after Rome, Lystra appears to have abstained from that path. It did not become heavily Romanized but continued to maintain its unique identity and heritage of the Lycaonian people. Latin was the official language of Lystra as a Roman colony and Greek would have been the every day language of the Romans, but it appears the local tongue of the Lycaonians remained in use among the native residents of the city.

Unlike the ambitions of other Roman colonies in the empire, Lystra did not seem to aspire to gain status and prestige. Rather, it has been described by scholars as “an active and prosperous community, not one to care much for its status as a Roman colony, a thriving, rather rustic market town” (Barbara Levick, Roman Colonies in Southern Asia Minor [Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1967], 154). Lystra can be thought of as a city of commerce likely with a strong native Lycaonian culture. One might say that it was a city that maintained its root even when foreign settlers (Roman militia) came to town and started running the show.

Within Lystra there was certainly would have had a diversified population after becoming a Roman colony. The city residents would have been composed of the Roman aristocracy, Gentile immigrants from around the empire, and Lycaonian natives. There would also have been a natural cast system with the Roman settlers at the top and the Lycaonian natives at the lower end. In addition, there is no evidence for the establishment of a Jewish presence in Lystra in the 1st century A.D. It appears that the city might have been entirely pagan when the missionary preachers (Barnabas and Paul) first arrived.

A Christian church would be planted in Lystra and in the coming centuries the community would grow and thrive. This is evident because in the beginning of the 4th century, bishops from Lystra are recorded attending the Council of Nicea (325 A.D.). Moreover, the Christian community continued to have a strong presence in the city through the first millennium A.D. as bishops of Lystra are also noted as being present at the Council of Constantinople (381 A.D.), Chalcedon (451 A.D.), and Second Constantinople (879 A.D.).

Archaeological Significance

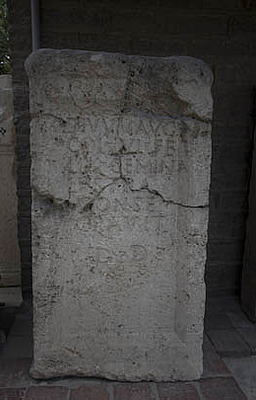

Lystra is thought to be located at the tel Zoldera H�y�k near modern Hatunsaray in Turkey, the tel has not been excavated and there is little for the visitor to see except a large mound with some stone fragments scattered around. Scholars identify this location at Lystra on account of a stone inscription that was found near the tel in 1885. The Latin inscription reads:

DIV. VM. AVG. COL. IVL. FELIX. GEMINA. LVSTRA. CONSECRAVIT. D.D.Divum Aug(ustum) Col(onia) Iul(ia) Felix Gemina Lustra consecravit d(ecreto) d(ecurionum)

The inscription uses the full formal name of the city Colonia Iulia Felix Germina Lustra (“The Colony of Julia Felix Germina Lystra”)

Also near the tel of Zoldera H�y�k, two other inscriptions were discovered in 1909. They confirm the existence of cult followings for the gods of Zeus and Hermes at Lystra. The inscriptions read as follows: (1) “Kakkan and Maramoas and Iman Licinius priests of Zeus”; (2) “Toues Macrinus also called Abascantus and Batasis son of Bretasis having made in accordance with a vow at their own expense (a statue of) Hermes Most Great along with a sun-dial dedicated it to Zeus the sun-god.” The Zeus-Hermes cult combination was not novel but the archaeological evidence found at Zoldera H�y�k has further substantiated the biblical record regarding these gods when Barnabas and Paul visited the city (see Biblical Significance below). Cult combinations were also fairly common as every locality in the ancient world worshiped deities that were considered to be the patron gods/goddess of that area. Apparently, at Lystra Zeus and Hermes were likely among the favored gods that were worshiped by the citizens and thought to be the protectors and overseers of their land.

Furthermore, literary evidence contemporary with Barnabas and Paul refer to a myth related to Zeus and Hermes near Lystra. Ovid, the famous Roman poet (43 B.C. – 17/18 A.D.), mentions a tale of these two gods appearing to an old couple living in the neighborhood of Lystra in his poem “Metamorphoses” (8.611-724). As the poem goes, Zeus and Hermes visited towns and villages in the region, appearing in human form. However, they did not receive any hospitality from anyone until they came to the home of the poor and elderly Baucis and Philemon. Zeus and Hermes were invited in and were given the last rations of the food left and provided with the most comfort available in the house. But, when Baucis began preparing the meal for their guests there was more and more food and the wine kept “welling up of itself.” Then, Baucis and Philemon became very afraid because of the miracle and so Zeus and Hermes revealed themselves and explained how they were the only couple in the area who welcomed them into their home. Due to their act of hospitality, they would be blessed while the rest of the region would be destroyed.

Biblical Significance

Lystra is one of the destinations in central Asia Minor mentioned in Paul's first missionary journey after he and Barnabas had traveled through Antioch of Pisidia and Iconium. Barnabas and Paul had encountered great resistance in those cities and so moved on to the near-by city of Lystra (as well as Derbe) and they began to preach the gospel there just like they did previously (Acts 14:6-7).

While venturing through the streets in Lystra, Paul and Barnabas found a man who had deformed feet since he was born and had never walked a day in his life. Paul began to preach the gospel to him and then realized that the man had faith that he could be healed. Without a moment's delay, Paul calls out to the man saying, “Stand up!” and the man then immediately got up and began walking (14:8-10). The idea was not that the man had simply the will-power or courage to stand, but rather this was an instantaneous healing and the man's feet gained strength and presumably the deformation in his feet was corrected for him to be able to stand and support himself and then begin walking.

Such a miracle astonished the local people. After seeing this wonder performed before their eyes, they cried out in their local dialect (which was probably the Lycaonian tongue of the native people) that Paul and Barnabas must be gods who have come to them in human form. Among themselves, the people determined that Barnabas must be Zeus and Paul must be Hermes because Paul was the principal speaker for the pair (14:11-12). It is important to note that the names of Zeus and Hermes in Roman mythology were analogous to Jupiter and Mercury in Greek mythology.

For the people of Lystra to speak to Barnabas and Paul in their native tongue indicated, to some degree, a lack of Hellenization/Romanization (the Romans spoke Latin and Greek and made Latin the official government language and Greek the common language of the people). This further supports the fact that at least some portion of the native Lycaonian culture remained active in Lystra even after becoming a Roman colony.

With regards to the response of the people at Lystra, one might think that the identification of Barnabas and Paul as Zeus and Hermes would make more sense the other way around, that Paul would be Zeus and Barnabas would be Hermes. But in ancient mythology (Greek and Roman), the lesser god was the messenger and therefore did the speaking for the greater god. Hermes was a god of lesser status than Zeus and actually plays the role of being Zeus' messenger who carries and delivers his decrees to humans and other gods. Since Paul was the speaker for the pair of them, it would only be natural that the people of Lystra would assume Barnabas was the greater god, Zeus, and subsequently associate Paul with the lesser god Hermes.

However, why did the people think that Barnabas and Paul were specifically Zeus and Hermes? Why not another familiar pair of ancient gods? As explained above, there was a local legend about Zeus and Hermes performing miracles in the area and they were looked at as the patron deities of Lystra. Likely, the priest and cult following of Zeus at Lystra would have been familiar with these tales and would have expected any supernatural event in their city as coming from their patron gods.

After labeling Paul and Barnabas as Zeus and Hermes, the local priest of Zeus organized bulls and oxen and wreaths of flowers to be brought to the town gate for sacrifices to them in worship of their presence among the people and for coming so graciously into their midst and performing this great miracle (14:12-13).

In a distressful response to the aberrant desires of the people to offer sacrifices to them as gods, Barnabas and Paul tore their clothes in dismay and protest, and began running around the crowd shouting, “Why are you doing this?” Barnabas and Paul's argument was that they had come to preach the gospel to them exactly for the reason of turning them away from worshiping false gods, like they were presently engaged in doing. They were come to bring the people to know the living God who is the great Creator of all things and who has proven his existence by giving the people rain, food, and joyful hearts. But no matter how hard Barnabas and Paul were working to make the people stop, such words fell on deaf ears, for the people were so enthralled by the miracle and were so enthusiastic to offer sacrifices in honor of Barnabas and Paul that they paid little, if any, attention to what they were trying to tell them (14:14-18).

This is a great example of how people can be so stubborn and entrenched in tradition that they miss the whole point of something the Lord is trying to reveal to them. Maybe we are not trying to sacrifice to ancient gods, but maybe we are bent only listening (as an authority) to certain people. Maybe we have made up our mind about something so adamantly that we are beyond re-considering regardless of what we learn. Maybe we don't like to change and therefore are content with where we are presently at in our faith and have no desire to grow. I think an appropriate illustration is the typical mindset of church-going Christians. Most Christians are part of a church that was started by one person who had one way of thinking about faith and interpreting the Bible. Other people liked that person's ideas and teaching and decided to adopt them and follow his ways. This is how denominational churches start and how the culture generally operates. Don't get me wrong. Denominational churches are not completely bad; I am simply pointing out an infectious thought-process that occurs within them.

When a tradition infiltrates an organization (like a church) on a very deep level, that organization becomes defined by that tradition, and therefore, in order for that tradition to continue, the exact system of beliefs and teaching must be perpetuated. But when people say they follow the teachings of an individual (not referring to Jesus or apostolic examples in Scripture), they find themselves with divided loyalties. They cannot be both loyal to Scripture (in the absolute sense) AND loyal to the Christian leader because no person can have two masters. The only option to hold both at the same time is to let the leader's view of Scripture become our view. But as a consequence from that decision, we no longer are loyal to Scripture. It is a crafty deception when we find ourselves thinking that one person must be right because in order for that person to always be right, their views must be the only right views. And, to maintain that position of rightness in a person's eyes, one's allegiance must be to the leader, rather than God and revealed Scripture.

What happened next was that some Jews from Antioch of Pisidia and Iconium came to Lystra and opposed the preaching of Barnabas and Paul. The Jews convinced the towns people to turn against them, and in their spite and anger they began stoning Paul. They eventually dragged him outside the city presuming he was dead. However, when the disciples gathered around Paul's body, he got up and went back into the city with them (14:19-20). For the people of Lystra to go from uncontrollable urges to offer sacrifices and worship Barnabas and Paul, to picking up stones and trying to kill them, they must have been won over and then manipulated by the Jews from Antioch and Iconium. Probably the recently arrived Jews helped convince the people of Lystra that Barnabas and Paul were not Zeus and Hermes (because otherwise the people would never have tried to harm them), but they also must have incited a cause for the people to desire to execute them. Maybe killing Barnabas and Paul was the remuneration they thought they needed to do in order to recompense the gods for offering sacrifices to mere humans in their stead. But needless to say, Barnabas and Paul did not stick around Lystra very long. They departed the following day for Derbe, another city in the region of Lycaonia.

Paul also mentions these harsh experiences of persecution in 2 Tim 3:11. What is interesting is that when Barnabas and Paul finished preaching at Derbe, they retraced their steps back through Lystra, Iconium, and Antioch (places where they had all experienced suffering for the sake of the gospel). At each place Paul encouraged the believers and conveyed to them how every person who will live a godly life in Christ will suffer persecution and evil people and imposters will flourish (3:12-13).

Lastly, the disciple named Timothy is noted as being from Lystra and have a good report of the believers at Lystra and Iconium (Acts 16:1-2). Timothy would become one of Paul's closest associates and co-workers in the gospel. Paul would affectionately refer to Timothy as “my true son in the faith” (1 Tim 1:2).